The Salt Mine of Wieliczka – Krakow’s World-class Attraction. One travelled Frenchman observed in the 18th century that Krakow’s Wieliczka salt mine was no less magnificent than the Egyptian pyramids. Millions of visitors, the crowned heads and such celebrities as Goethe and Sarah Bemhardt among them, have appeared to share his enthusiasm when exploring the subterranean world of labyrinthine passages, giant caverns, underground lakes and chapels with sculptures in the crystalline salt and rich ornamentation carved in the salt rock. They have also marveled at the ingenuity of the ancient mining equipment in the Wieliczka salt mine. And the unique acoustics of the place have made hearing music here an exceptional experience.

The Wieliczka Salt Mine, nowadays practically on the Southeast outskirts of Krakow, has been worked for 900 years. It used to be one of the world’s biggest and most profitable industrial establishments when common salt was commercially a medieval equivalent of today’s oil. Always a magnet, since the mid-18th century Krakow’s Wieliczka salt mine has become increasingly a tourist attraction in the first place. Today visitors walk underground for about 2,000 m in the oldest part of the salt mine and see its subterranean museum, which takes three hours or so.

Nine centuries of mining in Wieliczka produced a total of some 200 kilometres of passages as well as 2,040 caverns of varied size. The tourist route starts 64 m deep, includes twenty chambers, and ends 135 m below the earth surface, where the world’s biggest museum of mining is located with the unique centuries-old equipment among its exhibits.

Occasionally concerts and other events take place in the Wieliczka mine’s biggest chambers.

There is a sanatorium for those suffering from asthma and allergy situated 135 meters deep underground in the Wieliczka Salt Mine.

Deep underground in Poland lies something remarkable but little known outside Eastern

Europe. For centuries, miners have extracted salt there, but left behind things quite startling

and unique. Take a look at the most unusual salt mine in the world.

From the outside, Wieliczka Salt Mine doesn’t look extraordinary. It looks extremely well kept

for a place that has not mined any salt for over ten years but apart from that it looks ordinary.

However, over two hundred meters below ground it holds an astonishing secret. This is the

salt mine that became an art gallery, cathedral and underground lake.

It may feel like you are in the middle of a Jules Verne adventure as you descend in to the depths of the world. After a one hundred and fifty meter climb down wooden stairs the visitor to the salt mine will see some amazing sites. About the most astounding in terms of its sheer size and audacity is the Chapel of Saint Kinga. The Polish people have for many centuries been devout Catholics and this was more than just a long term hobby to relieve the boredom of being underground. This was an act of worship.

Situated in the Krakow area, Wieliczka is a small town of close to twenty thousand inhabitants. It was founded in the twelfth century by a local Duke to mine the rich deposits of salt that lie beneath. Until 1996 it did just that but the generations of miners did more than just extract. They left behind them a breathtaking record of their time underground in the shape of statues of mythic, historical and religious figures. They even created their own chapels in which to pray. Perhaps their most astonishing legacy is the huge underground cathedral they left behind for posterity

Still, that doesnt stop well over one million visitors (mainly from Poland and its eastern

European neighbors) from visiting the mine to see, amongst other things, how salt was mined

in the past.

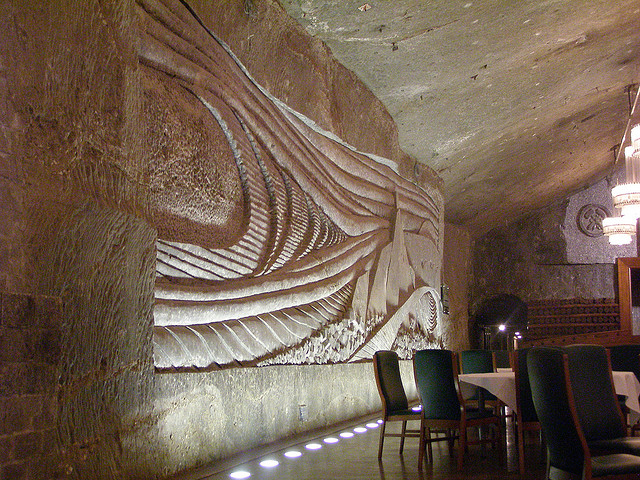

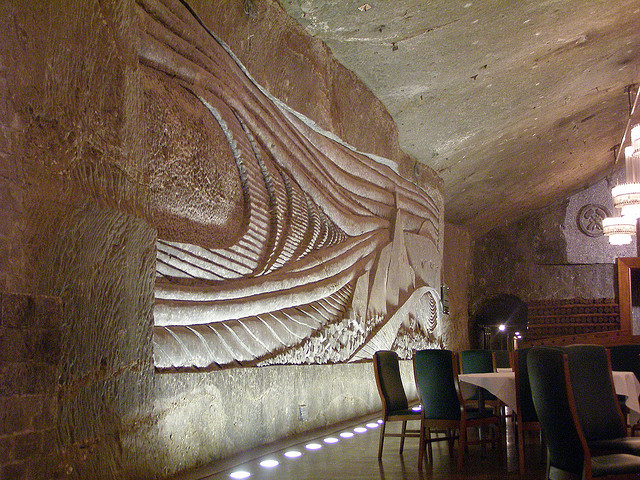

These reliefs are perhaps among some of the most iconographic works of Christian folk art in the world and really do deserve to be shown. It comes as little surprise to learn that the mine was placed on the original list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites back in 1978.

Amazingly, even the chandeliers in the cathedral are made of salt. It was not simply hewn from the ground and then thrown together; however, the process is rather more painstaking for the lighting. After extraction the rock salt was first of all dissolved. It was then reconstituted with the impurities taken out so that it achieved a glass-like finish. The chandeliers are what many visitors think the rest of the cavernous mine will be like as they have a picture in their minds of salt as they would sprinkle on their meals! However, the rock salt occurs naturally in different shades of grey (something like you would expect granite to look like).

Another remarkable carving, this time a take on The Last Supper. The work and patience that must have gone in to the creation of these sculptures is extraordinary. One wonders what the miners would have thought of their work going on general display? They came to be quite used to it, in fact, even during the mines busiest period in the nineteenth century. The cream of Europe’s thinkers visited the site, you can still see many of their names in the old visitors books on display.

To cap it all there is even an underground lake, lit by subdued electricity and candles. This is perhaps where the old legends of lakes to the underworld and Catholic imagery of the saints work together to best leave a lasting impression of the mine. How different a few minutes reflection here must have been to the noise and sweat of everyday working life in the mine.

Not all of the statues have a religious or symbolic imagery attached to them. The miners had a sense of humor, after all! Here can be seen their own take on the legend of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. The intricately carved dwarves must have seemed to some of the miners a kind of ironic depiction of their own work.

The religious carvings are, in reality, what draw many to this mine ג€“ as much for their amazing verisimilitude as for their Christian aesthetics. The above shows Jesus appearing to the apostles after the crucifixion. He shows the doubter, Saint Thomas, the wounds on his wrists.

Not all of the work is relief-based. There are many life sized statues that must have taken a considerable amount of time ג€“ months, perhaps even years ג€“ to create. Within the confines of the mine there is also much to be learned about the miners from the machinery and tools that they used ג€“ many of which are on display and are centuries old. A catastrophic flood in 1992 dealt the last blow to commercial salt mining in the area and now the mine functions purely as a tourist attraction. Brine is, however, still extracted from the mine ג€“ and then evaporated to produce some salt, but hardly on the ancient scale. If this was not done, then the mines would soon become flooded once again.

The miners even threw in a dragon for good measure! Certainly,they may have whistled while they did it but the conditions in the salt mine were far from comfortable and the hours were long ג€“ the fact that it was subterranean could hardly have added to the excitement of going to work each morning.